Here at Leaning Technologies, we love WebAssembly. Its safe, efficient, and fast

properties have allowed us to run complicated, large codebases right in users’

browsers, such as Minecraft, IntelIJ Idea

as well as

Linux virtual machines

.

But, compared to native platforms, WebAssembly has a caveat that makes it sometimes difficult to work with.

WebAssembly has no memory protection like one would have on native. This means we get little to no feedback if our program tries to access memory it is not allowed to access. Leaving us oblivious to the presence of such an error. And even if we are aware of it, we have no easy way to locate it, often leading to long debugging sessions.

And perhaps to add insult to injury, we write our software using C and C++, which offer lots of efficiency, but also lots of avenues for introducing memory errors.

On native, this problem has been slightly relieved by the development of tools that can detect these memory errors (such as Valgrind). But on the browser, this doesn’t really exist.

So we set out to solve that.

AddressSanitizer to the rescue!

Cheerp, as of recently, supports compiling code with ASan (AddressSanitizer).

ASan is a tool that can be used to detect common programming errors such as:

- Use after free

- Heap buffer overflow

- Stack buffer overflow

- Use after return

- Use after scope

- Initialization order bugs

- Memory leaks

All while slowing down a program about 2x on average, which is noticeable, but still allows manual testing.

An example

int main() { int* p = 0; return *p;}When compiled and run on my machine I’m greeted with the following message:

Segmentation fault (core dumped)Informing me that my code tried to do something it wasn’t allowed to.

Compiling that code to Wasm with Cheerp and running it is less helpful:

$ /opt/cheerp/bin/clang test.c$ node a.outGiving us absolutely no hint that our code has a bug. As noted in the beginning, this is because WebAssembly has no memory protection.

Let’s try that again, this time compiling our code with ASan:

$ /opt/cheerp/bin/clang test.c -cheerp-pretty-code -fsanitize=address$ node a.out===================================================================1==ERROR: AddressSanitizer: unknown-crash on address 0x00000000 at pc 0x00017903 bp 0x00000000 sp 0x00100ffcREAD of size 4 at 0x00000000 thread T0 #0 0x17903 in main (main+0x17903) #1 0x20493 in _start (main+0x20493) #2 0x800001ac in <unknown function> main:428

Address 0x00000000 is a wild pointer inside of access range of size 0x00000004.SUMMARY: AddressSanitizer: unknown-crash (main+0x17903) in mainShadow bytes around the buggy address:=>0x00000000:[fe]fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe 0x00000080: fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe 0x00000100: fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe 0x00000180: fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe 0x00000200: fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe 0x00000280: fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe fe feShadow byte legend (one shadow byte represents 8 application bytes): Addressable: 00 Partially addressable: 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 Heap left redzone: fa Freed heap region: fd Stack left redzone: f1 Stack mid redzone: f2 Stack right redzone: f3 Stack after return: f5 Stack use after scope: f8 Global redzone: f9 Global init order: f6 Poisoned by user: f7 Container overflow: fc Array cookie: ac Intra object redzone: bb ASan internal: fe Left alloca redzone: ca Right alloca redzone: cb==1==ABORTINGThis time, when we run our program, we instead get a detailed error report

informing us that we tried to read 4 bytes from the null address in the function main.

How does it work?

ASan keeps track of what memory the program is and isn’t allowed to access, and inserts checks before each store or load like this:

Before:

*address = ...; // or: ... = *address;After:

if (IsPoisoned(address)) { ReportError(address, kAccessSize, kIsWrite);}*address = ...; // or: ... = *address;*Example from the ASan documentation

“Poisoned” here means that the program is not allowed to access that memory.

How does it really work?

As I see it, there are three big parts to ASan:

- Memory mapping

- Instrumentation

- Runtime library

If we really want to understand ASan, we’ll have to go through them one by one.

*Please note that parts of this explanation are still simplified. If you really

want to understand ASan then I’d recommend reading the original paper

introducing the concept

and looking into the source code in LLVM.

Memory mapping

ASan splits the virtual address space into 2 disjoint classes:

- Main application memory

- Shadow memory

Main application memory is the memory that we all love and use. Shadow memory is used internally by ASan to keep track of which parts of the main memory the program is allowed to access (it “shadows” the main memory). To be exact, for every 8 bytes of application memory, a byte is used to store how many of those 8 bytes are accessible:

- All 8 bytes are unpoisoned. The shadow value is 0

- All 8 bytes are poisoned. The shadow value is negative

- First

kbytes are unpoisoned, the rest8-kare poisoned. The shadow value isk

The shadow memory will then be placed at some known location so that it can be loaded on runtime to check if an address is poisoned or not.

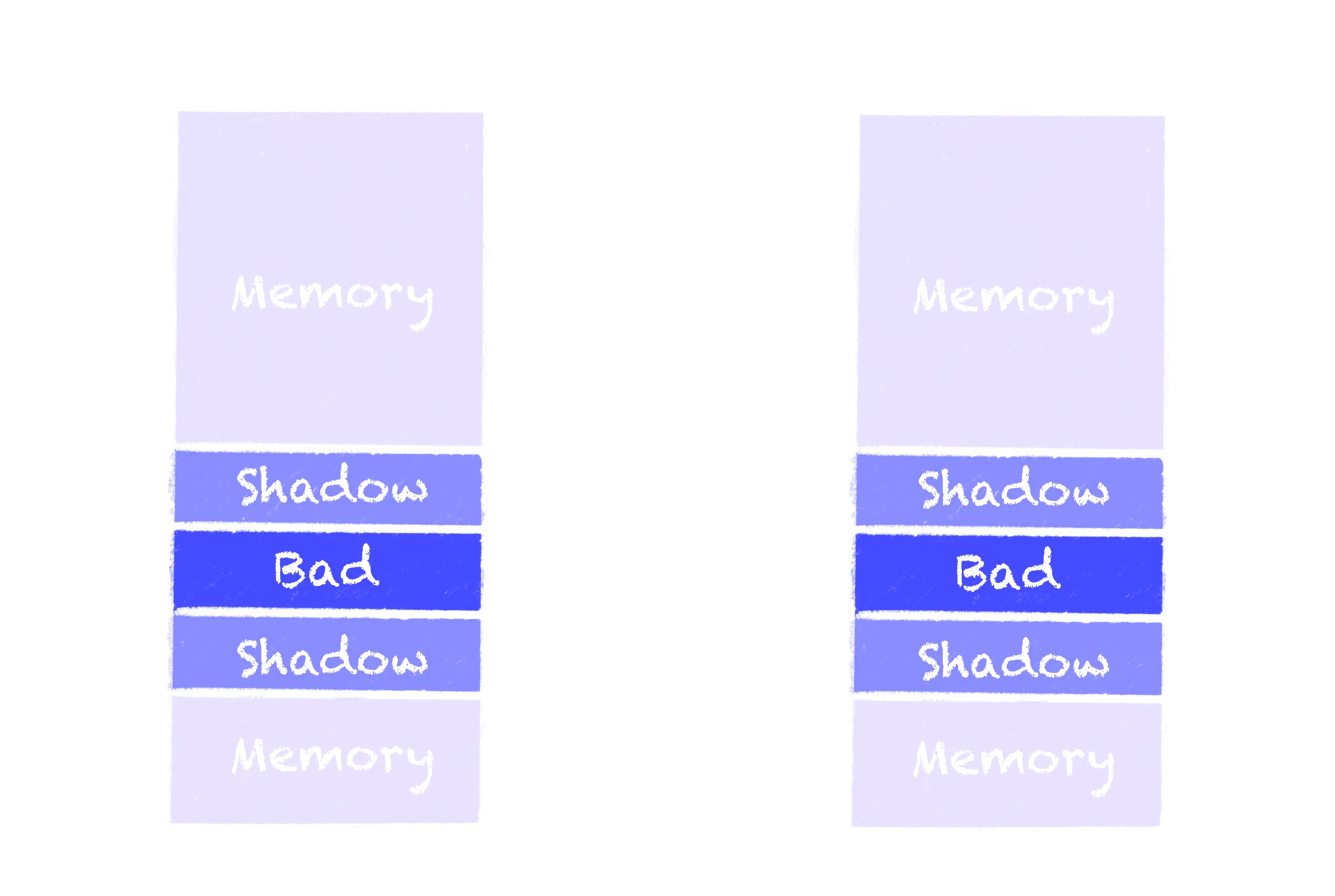

You might be wondering how ASan will protect its shadow memory. On native it usually maps the area of the shadow memory that shadows the shadow memory to protected memory, making the address space look something like this:

This will cause the program to crash when trying to check if it was allowed to read the shadow memory. But as I said in the introduction, WebAssembly does not have this kind of memory protection. So what we do instead is poison the entire shadow region.

Instrumentation (load and stores)

Now that we know how/where to check that we can access some memory address, we can make the instrumentation a bit more concrete:

For 8-byte accesses, the instrumentation looks like this:

byte *shadow_address = MemToShadow(address);byte shadow_value = *shadow_address;if (shadow_value) { ReportError(address, kAccessSize, kIsWrite);}For 1-, 2- or 4- byte accesses:

byte *shadow_address = MemToShadow(address);byte shadow_value = *shadow_address;if (shadow_value && ((address & 7) + kAccessSize > shadow_value)) { ReportError(address, kAccessSize, kIsWrite);}*This is a slightly modified example from the ASan documentation

Instrumentation (stack)

For stack allocations, the compiler will insert so called “redzones” (basically poisoned memory regions) before and after the allocation. For example, the following c++ code:

void foo() { char a[8]; ... return;}After instrumentation, it will look something like this:

void foo() { char redzone1[32]; // 32-byte aligned char a[8]; // 32-byte aligned char redzone2[24]; char redzone3[32]; // 32-byte aligned int *shadow_base = MemToShadow(redzone1); shadow_base[0] = 0xffffffff; // poison redzone1 shadow_base[1] = 0xffffff00; // poison redzone2, unpoison 'a' shadow_base[2] = 0xffffffff; // poison redzone3 ... shadow_base[0] = shadow_base[1] = shadow_base[2] = 0; // unpoison all return;}*Example from the ASan documentation

Something similar happens to global values, which I’ll not go into detail here.

Runtime library

The last part of the puzzle is the runtime library. This replaces the functions

malloc and free, as well as a few other standard library functions, and also

adds error reporting functions.

The new malloc will allocate the requested amount with redzones around it.

The new free will poison the entire region and put the chunk into

something called “quarantine” (which basically means it’s less likely to be

returned from a call to malloc)

Combining these concepts together gives us the ASan tool.

Trophies

Although ASan is actually quite a simple system, it has already found the following bugs in our products:

- 2x Use after free in our tests

- 1x Use after free in CheerpX

- 1x Nullptr dereference in CheerpX

- 1x Undefined behavior in CheerpJ

Give it a try!

ASan is now included in our nightly builds of Cheerp. You can download Cheerp

here. For Debian/Ubuntu, consider using our nightly PPA

.

If you want more details on how to use ASan for Cheerp or Cheerp itself, check

out the Cheerp documentation.

For further support make sure to join our Discord where you will find Leaning Technologies core developers. We are always happy to help!

We hope you will enjoy using Cheerp. See you soon!